Most people who have spent any time in the area will be familiar with the People’s Republic of Stokes Croft. From their base on Hillgrove Street, a stone’s throw from Hamilton House, they oversee Jamaica Street Studios and Stokes Croft China, and are also active in the Bearpit.

Most people who have spent any time in the area will be familiar with the People’s Republic of Stokes Croft. From their base on Hillgrove Street, a stone’s throw from Hamilton House, they oversee Jamaica Street Studios and Stokes Croft China, and are also active in the Bearpit.

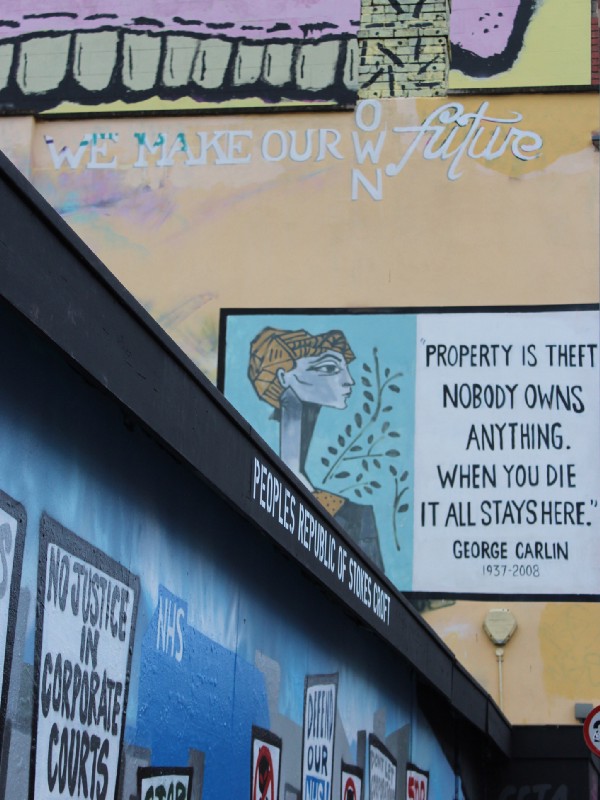

Over the years, much of their work has gone into making Stokes Croft into an outdoor gallery — “filling in the gaps in a gap-tooth smile”, as founder Chris Chalkey put it. Chris has been active in the area since the days when “the whole of Stokes Croft looked like a bomb site, it was 30% dereliction and was the kind of place where you would look down and neither to the left nor right until you got past the Polish church going north or to the hospital going in the opposite direction.”

Originally the owner of a wholesale china and glassware business based in Montpelier, Chris came into the possession of a building that had laid derelict on Jamaica Street for a years and was sold for “a pittance”. He became part of a space “which was then filled with squatting artists, in a building that somebody like myself would never imagine that they could have a share in.”

Originally the owner of a wholesale china and glassware business based in Montpelier, Chris came into the possession of a building that had laid derelict on Jamaica Street for a years and was sold for “a pittance”. He became part of a space “which was then filled with squatting artists, in a building that somebody like myself would never imagine that they could have a share in.”

After his business went bust, he started turning his attention towards the other empty buildings around the area. What began with painting anti-consumerist slogans on billboards and walls gradually morphed into a political conflict with Bristol City Council over who should wield control over neglected spaces in the area.

We started to joke about the role of the state. The role of the council was to stop things happening. Everything was on tamp down. We talked about Ealing comedies, Passport to Pimlico, where one small part of London had declared independence from the rest of the city, and a germ of an idea developed from there.

But while PRSC’s work has been central to the area’s transformation into the creative heart of Bristol, Stokes Croft now faces the same problems faced by artistic and cultural hubs everywhere:

Seeking to improve the area necessarily means that people become more interested in it, and the simple law of supply and demands means that it becomes more attractive. This is traditionally what happens when artists move into an area. So there’s an inevitability under the standard market conditions that gentrification will take place.

With the future of spaces like Hamilton House in doubt, and a wider context of rising prices in central Bristol, PRSC have been putting forward a radical solution to prevent the threat of corporate development in the area: forming a community land trust. Land trusts aren’t a new idea — they have deep roots in many parts of the world, from the post-war Garden City movement in the UK, the Gramdan village system in India, and initiatives for community housing that emerged from the African-American civil rights struggle in the 1960s. With the deepening of the housing crisis in the UK, they are again becoming popular.

The basic idea would be for local people to “set up an organisation that would have the capacity to own property communally”, This would in turn create “a community of interest” which could protect important local cultural spaces and landmarks from market forces.

Stokes Croft is already home to a successful citizen’s media project (The Bristol Cable) as well as a local currency, the Bristol Pound. With such an array of creative talent, together with the neighbourhood’s long history of rebellion and non-conformity, PRSC see no reason why the area shouldn’t become a beacon of an alternative economic model, one in which shared artistic and cultural spaces are protected, and the area’s role as a cauldron of experimentation remains intact. Blog by Coexist CIC